Geopolitical tensions, from the Middle East to the US-China rivalry, are reshaping global trade dynamics. While decoupling seems inevitable, the reality is a strategic reorganization rather than a total breakdown of globalization.

With the re-election of Donald Trump, the system of international trade built over the post-war era has some powerful blows coming its way. Though the size, coverage and timing of incoming tariffs is not fully defined, the President had not waited to take office to threaten 25% blanket tariffs on Mexico and Canada should they fail to do enough to curb migrant and drug flows to the US. Historically, the US has been the chief sponsor of trade liberalization and is the largest end-market in the world, accounting for roughly a third of global consumption. Its views on trade matters greatly for the future of global trade. Is globalization about to enter a period of decline?

A longstanding backlash against Globalization

The backlash against globalization did not begin in November 2024. Arguably, it has been manifesting since the start of the 21st century, with the failure of the WTO Doha round. Brexit showed that even in the ever-expanding European project, integration was not irreversible. The trade war launched under the first Trump administration marked the first ramp-up of tariffs among major economies in the post-war era. The pandemic and the war in Ukraine showed the risks of relying on distant countries for key stages of the production process (be that distance geographical or geopolitical). The conflict in the Middle East has highlighted the potential impact of geopolitics on the logistics of global trade. And yet, though trade as a share of global GDP has been stagnant since the 2008 financial crisis, it has not quite gone into reverse.

New Trade blocs emerge amid fragmentation

However, this apparent stability masks the profound changes that are taking place. Chart 1 plots aggregate trade flows within and between groups of countries that gravitate noticeably towards or away from the Western sphere of influence. If we consider, on one side, a bloc of Western-aligned countries - including most NATO countries and economies such as Australia or the Republic of Korea - and on the other, countries that voted “against” or abstained in response to the first UN motion to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine we begin to see a pattern consistent with geopolitical fragmentation. At the core of this trend is the unraveling of the trade partnership between western countries on one side, and China and Russia on the other.

Data for the graph in .xls file

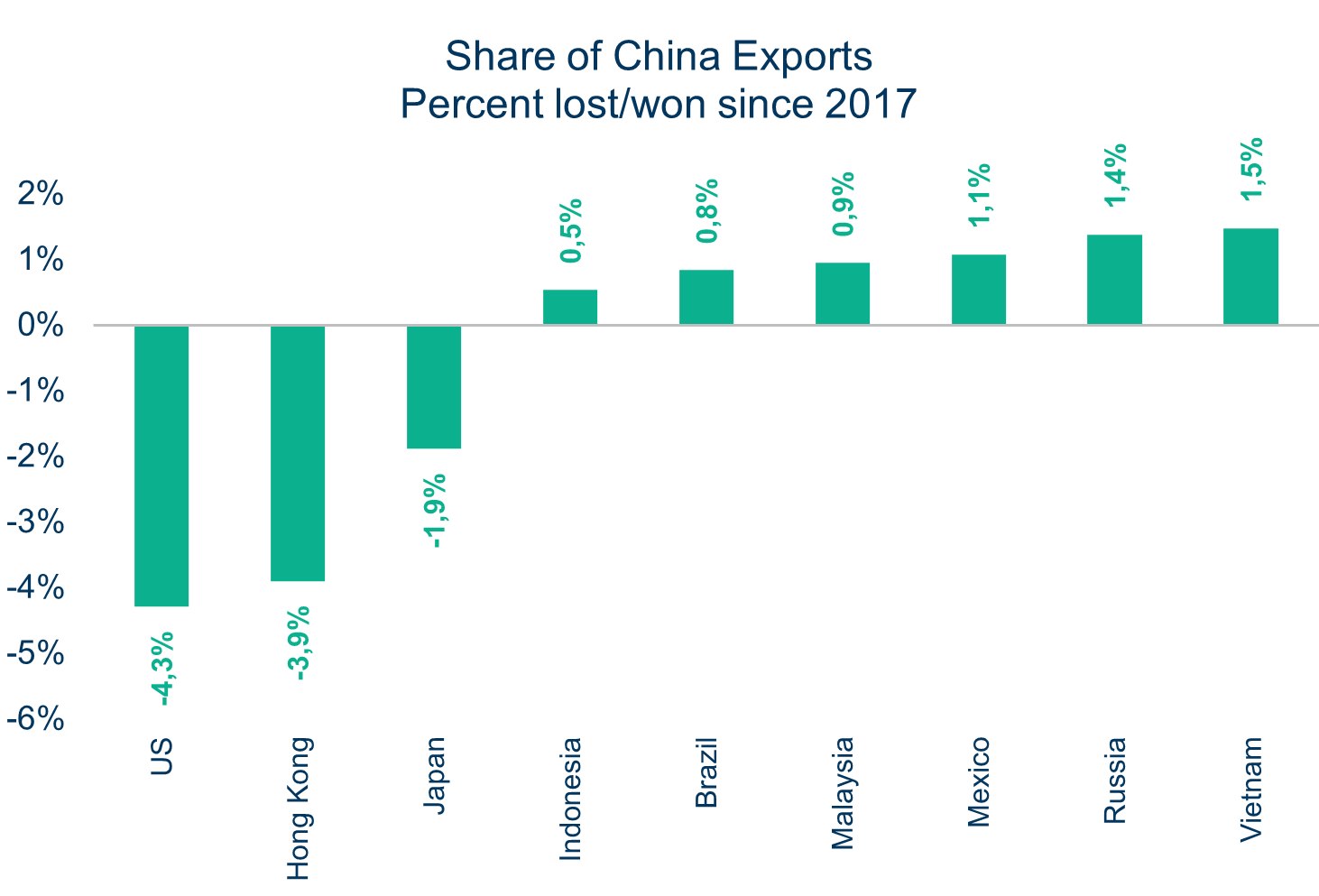

However, there is evidence that some of the previous trade between the EU and Russia survives, intermediated through third countries. Since early 2022, several former Soviet republics have experienced a marked increase in demand for goods from the EU, driven by trade in machinery and transport equipment. Similarly, when looking closely at US-China trade, the decoupling narrative gets more nuanced. Indeed, some of the countries that have gained ground as suppliers for the US are growing as destinations for Chinese exports (Charts 2 and 3). The presence of Mexico and Vietnam at the right end of both these charts is worthy of attention. For Vietnam, this role of intermediate step in supply chains linking the US and China is not new, but it appears to have been turbo-charged since the start of the trade war. Similar attributes make Vietnam and Mexico ideal candidates for friendshoring: access to US market, growing manufacturing base and transport infrastructure, competitive cost structure... In sum, when large and strongly integrated economies antagonize and enact measures to decouple trade, the relationship can survive (at least partially), intermediated by third countries that trade with both parties. Rather than be severed, the supply chain grows an additional link.

Data for the graphs in .xls file

Shifting trade routes: the new geography of commerce

At the same time, geopolitical trade barriers are transforming the physical way in which we trade globally. For instance, the EU’s imports bans on Russian crude oil (December 2022) and petroleum products (February 2023) have markedly boosted cargo traffic along the Northern Sea Route (NSR). Prior to these sanctions, the EU was a major export market for Russia, accounting for 46% of its crude oil exports in 2021. In response to the bans, Russia has redirected much of its oil exports to alternative markets, particularly China. These shifting trade patterns gave a boost to the NSR usage, which runs along Russia's Arctic coastline from the Kara Gate Strait to the Bering Strait, as it offers a shorter shipping route between Northern Europe and Asia compared to the traditional Suez Canal passage.

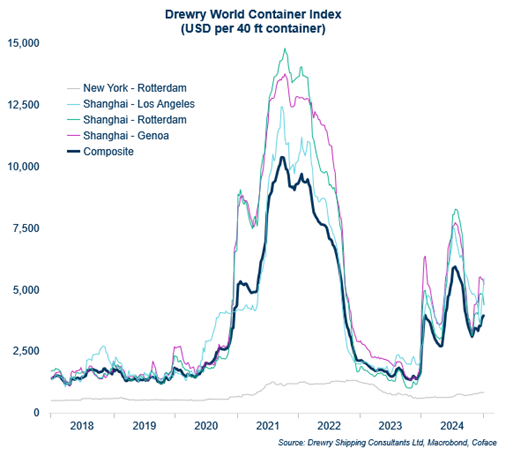

In their more extreme form, war, geopolitical tensions can trade’ security. The recent example of attacks on commercial vessels from the Red Sea to the Arabian Sea by Houthi rebels, in solidarity with Hamas, is striking. This has forced carriers to avoid to transit the Suez Canal, which traditionally handles 12% of global trade and 30% of container traffic. The number of ships going through the chokepoint plummeted by more 60% in the last quarter of 2024 compared to the same period in 2022. Instead, carriers opted for the Cape of Good Hope. In 2024, the Drewry World Container Index, which measures weekly ocean freight rates for 40-foot containers across seven major maritime lanes, was 2.4 times higher than the preceding year (Chart 4).

Data for the graph in .xls file

But, despite higher sea fret rates, volume reached record-high levels in 2024. Meanwhile, rail trade, which typically plays a secondary role, has stepped up and acted as a valuable release valve. The expansion of international rail trade has been facilitated by the development of several cross-border railway connections over the past decades, primarily driven by China's Belt and Road Initiative.

Global Trade: adaptation in the face of uncertainty

The resilience and adaptability of international trade stand out in light of the increasing frequency and intensity of geopolitical shocks. Despite these disruptions, global trade continues at significant levels, a testament to the emergence of connector countries and the agility of global merchandise transport systems. This suggests that the integrated global economy remains too profitable for market participants to permit a disorderly breakdown, even as international relations strain.

Want to know more?

> Download our Guide on the Future of Global Trade